Click go the shears, boys, Click! Click! Click!

Wide is his blow and his hands move quick

The ringer looks around and is beaten by a blow,

And curses the old snagger with the bare-bellied joe.

A traditional Australian folk song

Hand Shears By Cstaffa (Own work) via Wikimedia Commons

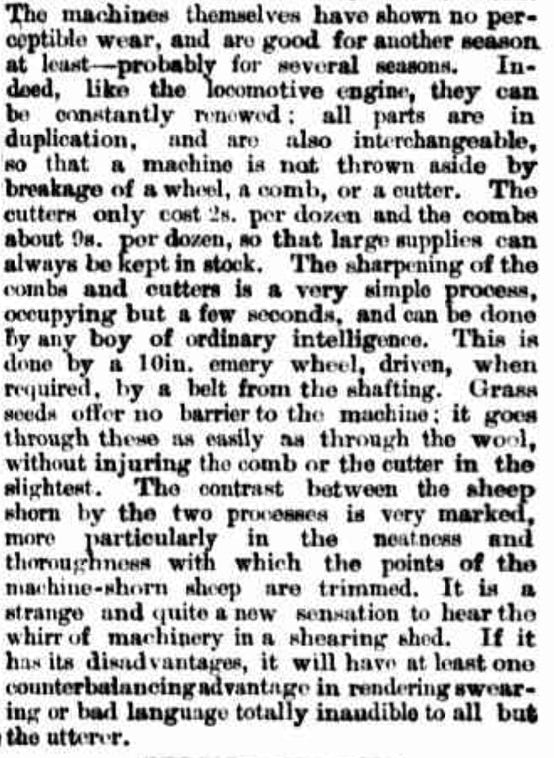

“Wool production was helped by a mechanical sheep shearing machine, invented by Frederick Wolseley (1837–99) when it was demonstrated around the country – to the delight of woolgrowers and the horror of blade shearers in the mid-1880s”

Australian farming and agriculture – grazing and cropping

http://www.australia.gov.au/about-australia/australian-story/austn-farming-and-agriculture

“Today, a shearer normally shears around 140 to 300 sheep a day. Teams of shearers travel from property to property during the season. A flock of 5000 probably requires a 4-stand shed with shearing machines and equipment for four shearers. Most sheep are shorn once a year and Merino wool grows about 7 to 10 cm in that time.”

More on Shearing and Cunnamulla history: http://www.cullyfest.com/cunnamulla/

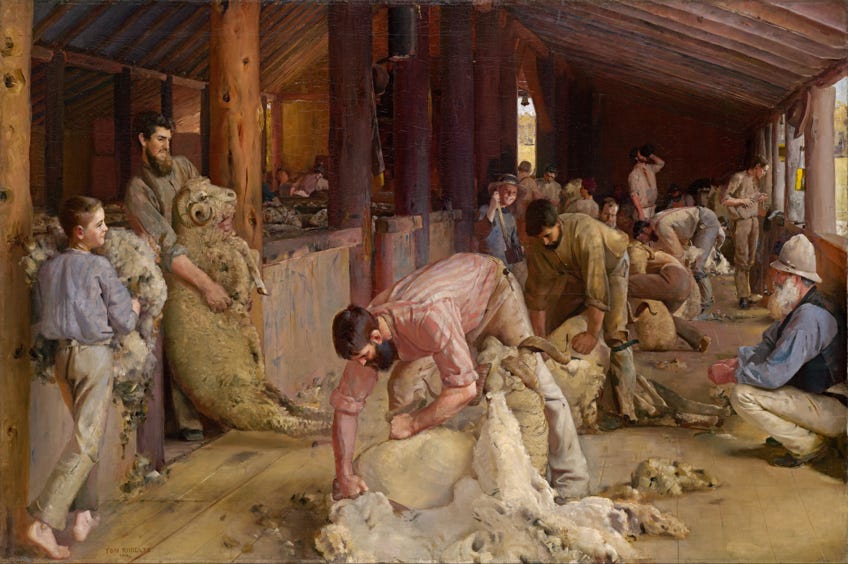

Shearing the Rams by Tom Roberts - National Gallery of Victoria. via Wikimedia Commons

The Brisbane Courier (Qld.) Mon 10 Oct 1887 Page 9 -TROVE

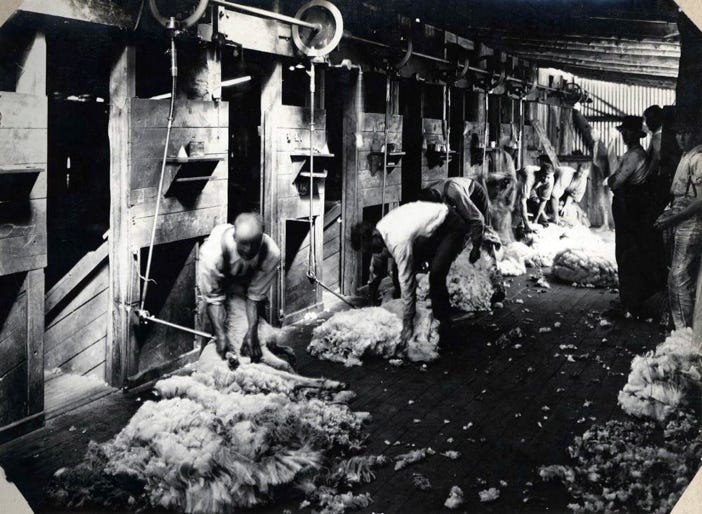

Photographic Collection from Australia (Sheep shearing Uploaded by Oxyman)

via Wikimedia Commons

Martin Pot (Martybugs at en.wikipedia),

via Wikimedia Commons

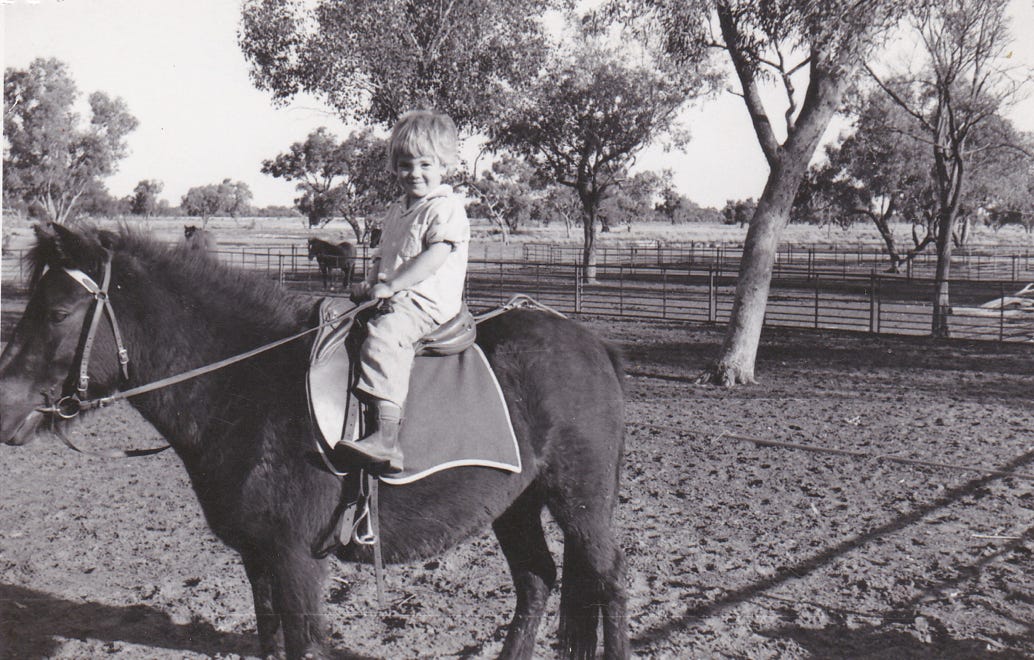

The working life on Werona was centred around the annual sheep husbandry activities: shearing, dipping, crutching, lamb marking and ear tagging. From when we were quite young we all had some helping role to play. Most tasks required that the mobs of sheep be mustered and brought to the yards adjoining the wool shed. When we weren’t old enough for the full day of mustering on horseback we kept an afternoon lookout from the back of the house for the incoming sheep. We were then allowed to ride out to help pen them up.

When there was an orphan lamb we got to fight over who gave them their bottles of milk. A large empty beer bottle with a teat on it was just right for the job. You had to hold the bottle firmly as all but the smallest and weakest lambs ‘butted’ the bottle as they sucked.

Sheep need to be dipped with insecticides that control fly strike or lice. Up near the pig pen, a short distance from the sheep yards, there was a disused old plunge dip that we were supposed to not play anywhere near. By the 1960s the work of dipping was done in the yards in the ‘new’ spray race. Our job here was to “stay right back away from the spray” and to help to keep the sheep moving up through the race.

Whenever sheep had to be moved through the pens we were allowed to use some ‘special tools’ that were kept on a high nail in a shed post. These valued, handcrafted objects were sheep rattles. They were constructed by first punching a nail hole into the centre of several of the tin lids from Log Cabin tobacco cans. Then a length of fencing wire was treaded through them and closed up into a circle about 12 cm in diameter. When it was shaken this made a fantastic low level rattle noise that moved sheep along without startling them.

Getting ready for shearing involved quite a lot of work. The wool shed and the shearers quarters all had to be cleaned and properly equipped. We had the important job of chasing the huge flock of resident pigeons out of the wool shed. Needless to say it was only ever a temporary eviction. As soon as the activity of shearing ceased the birds moved back into the shed and nested again in the rafters. While they made an awful mess with their droppings, and it took days to scrub out the shed, I still loved watching them. I thought, and I still do, that the rings of green and violet iridescent feathers around their necks are mesmerizingly beautiful.

Apart from shearing the sheep, there is a need for crutching them to prevent them getting flyblown. Crutching removes the wool from around the tail and between the rear legs of a sheep. When crutching is being done the sheep are often given a ‘wigging’ as well. Wigging removes wool from the head of sheep to prevent the wool from covering the sheep's eyes and making them "wool blind”.

Dad often did the crutching and wigging on his own, or with just one other man to help him. A benefit of this for us was a relaxation in the level of restrictions that were in place at shearing time. When there was a full shearing team in the shed we were always told to “stay out of the way of the men working”. Crutching time meant that we were allowed to be in the holding pen inside the shed and to help grab the next sheep to be shorn.

Crutching time also often afforded a splendid opportunity to raid the treacle tin. It was normally kept up on a high ledge near the engine that powered the overhead gear needed for the operation of the wool clipping handpieces. There was a long wide belt that ran in a loop from the engine to the end of the overhead machinery. In order to prevent this belt slipping Dad used to brush it generously with treacle. We were told “don’t eat that stuff it could give you a bellyache,” but of course we often did sample ‘just a bit of it’ if the tin was left down and we could get the lid off it!

By Cgoodwin (Own work), via Wikimedia Commons

State Library of New South Wales collection

Source: JE Duncan, Practical Points of Sheep Dipping, Bulletin No. 181, New Zealand Department of Agriculture.

via http://www.mfe.govt.nz

Wool Prices

“Throughout the 1930s, wool remained the cornerstone of Australian agriculture. Wool represented about 30 per cent of the total value of Australia's exports in the 1930s and this prosperity continued into the 1950s.”

Australian farming and agriculture – grazing and cropping http://www.australia.gov.au/about-australia/australian-story/austn-farming-and-agriculture

“Prosperity in the wool industry peaked in 1950-51 when the average greasy wool price reached 144.2 pence per pound, (equivalent to around $37 per kilogram in today's prices). This was nine times greater than the 1945-46 United Kingdom contract price, and almost 14 times greater than the average for the 10 seasons ending in 1938-39. This short-lived but extreme increase in price was due to the American demand for wool which was generated by the Korean War. During this period Australia was said to be 'riding on the sheep's back'. In 1950-51 the gross value of wool production had increased to 56% of the total value of production of all agricultural industries, compared with 17% in 1945-46. The increase in the price of wool during this period led to a sharp increase in sheep numbers, from 96 million in 1946 to 113 million in 1950.

The period of high prices did not last, and returns for wool quickly fell away. In 1951-52 returns were half those received for the previous year. While small rises sometimes occurred over the next 20 years, wool prices generally continued to fall until 1970-71, when the price fell to $0.60 per kilogram. By 1970-71 wool production contributed only 15% to total gross value of agricultural production. Over most of the 20 year period up to 1970, wool producers made reasonable profits compared with other agricultural industries, and the number of sheep and quantity of wool produced continued to increase. However, there were underlying concerns within the industry about the general decline of wool prices, and these resulted in a number of attempts to stabilise prices over the period. In 1970 when wool prices bottomed, a record 180 million sheep were producing approximately 890,000 tonnes of wool.

The wool industry - looking back and forward http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/featurearticlesbyCatalogue/1476D522EBE22464CA256CAE0015BAD4?OpenDocument

Frazer

- FRAZER - From Kingussie, Scotland, to Sydney, Australia.

- FRAZER - First to Cabramatta and then to Binda, New South Wales.

- FRAZER/MARKS/LAMB - Meeting the neighbours

- FRAZER/MARKS/LAMB - An Inn, Horse Races, and Gold;

- FRAZER - Bullock Drays and Bushrangers.

- FRAZER/MARKS - ‘Markdale’ - On the move again.

- FRAZER/MARKS - They made a long trek north.

- FRAZER - The Queensland story - By 1878 the Fraser family settled in Charleville.

- FRAZER/STEWART/DOODY - Charleville 1892 - Alexander Frazer married Agnes Jane Stewart.

- FRAZER - Wyandra 1905 - Alexander Jnr’s son, Alexander, works as a blacksmith.

- FRAZER - Wyandra 1915 - 1921 - The Great War and A Soldier’s Memorial.

- FRAZER - Will they still remember us?

- FRAZER/GRANT - Wyandra 1921 - 26 - A Marriage, and Christmas Mistletoe.

- FRAZER - Wyandra 1928 - A Fancy Dress Ball.

- FRAZER - Wyandra 1920s - Bullock Wagons to Tractors and Trucks.

- FRAZER - ‘Werona' via Bollon 1930s.

- FRAZER - Barcaldine 1930’s - ‘Avonslea’

- FRAZER - Barcaldine 1936 -1940s - ‘Avonslea’, Elm St. and a Flower Show.

- FRAZER - Brisbane 1950s - 1960s - West End and Coorparoo.

- FRAZER - Southport and Surfers Paradise.

- FRAZER - ‘Werona’ and ‘Beneree’ 1955 to 1970 - ‘Of drought and flooding rain’

- FRAZER - ‘Werona’ - Click go the shears

- FRAZER - Cunnamulla - “I can see the water tower!”

- FRAZER - Cunnamulla 1965 & 1966 - School Days

- FRAZER - ‘Werona’ - The bush hath friends to meet him

- FRAZER - ‘Werona’ - The magic of trees

- FRAZER - ‘Werona’ - A portrait of our chook yard

- FRAZER - ‘Werona’ - The moon is lonely in the sky

- FRAZER - Toowoomba - ‘Someplace Green’

- FRAZER Summary - Alexander Fraser & Margaret McBean to Alexander ('Sonny') Frazer.

- FRAZER 2016 ’Werona’ revisited

- FRAZER - Marks - Lamb - Stewart - Doody -The case is never closed.